How do books age?

A friend recently noted on social media that we write for our own generation. As we live and respond to the oddities of life, we address those physically or digitally connected to us. This is our primary audience because they share our “spacetime” and reference the same points of interest—political events, economic conditions, and artistic environments. This proximity gives communication its purest form: direct and unobstructed, requiring no annotations. We do not live in a vacuum, but in relation to our peers within a specific era; with them, at least, we share a common language.

This direct communication allows for deeper insights and stronger stories. The bond between an author and a contemporary audience shapes both parties. But what happens when this bond breaks?

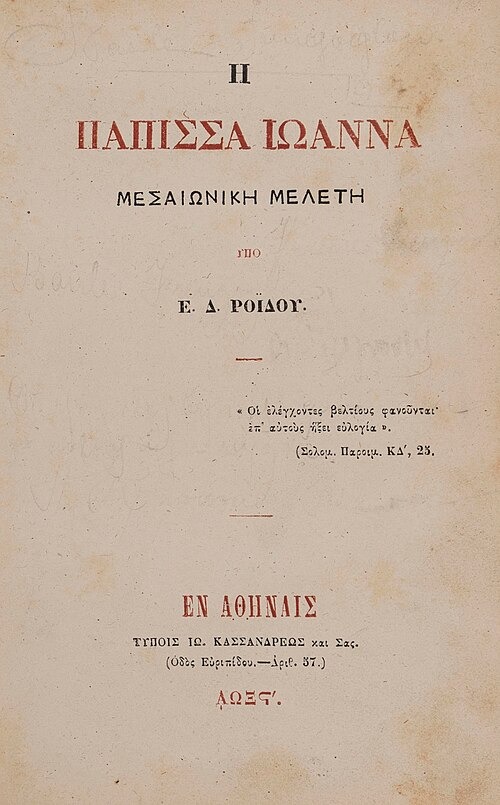

I just finished reading The Papess Joanne by Emmanuel Rhoides, a 19th-century Greek novelist. He wrote a fictional account of a woman who supposedly became Pope in the late 9th century. At the time, the book was well-received by the young, progressive, and newly formed Greek bourgeoisie, though it was loathed by the local Orthodox Church and conservatives.

It was a joy to read—not only for the plot, but primarily for the subtle style of the archaic Greek, the prose, the unexpected metaphors, and the fine sense of humor. I laughed a lot. It is no coincidence that The Papess Joanne is categorized as a classic.

At the same time, it feels like a museum object, removed from the fierce social clashes that once shaped a generation and embroiled clergy and politicians. The original passion and connection are gone. Those who value its charms today tend to be older, myself included. Like humans and machines, books age by the simplest and most accurate metric: they become increasingly less relevant to the current state of the world.