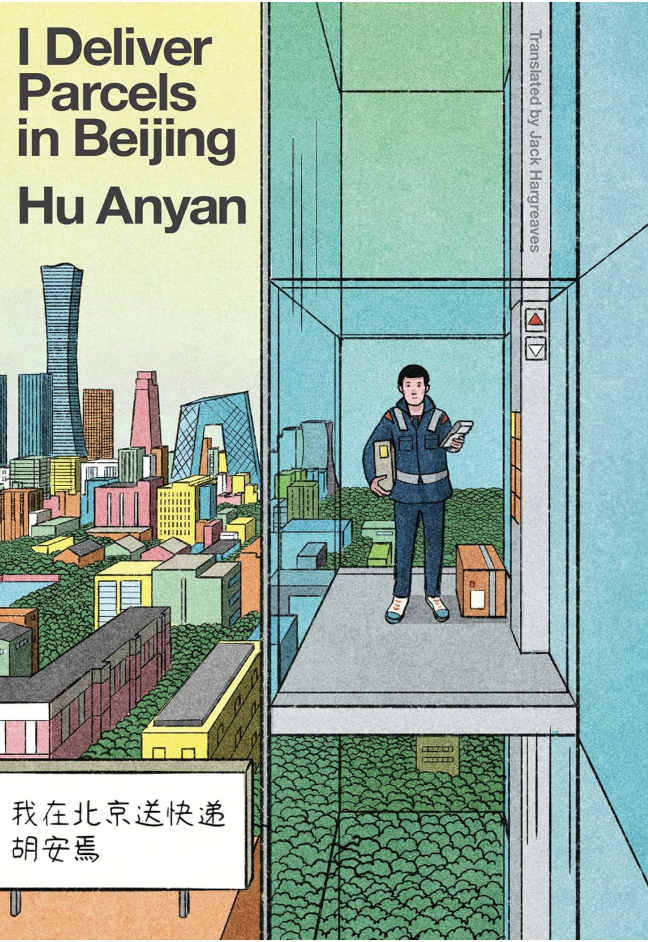

“I Deliver Parcels in Beijing”, a great view at everyday China.

Reading is one of the most enjoyable ways to learn about the world. One such experience has been “I Deliver Parcels in Beijing” over the last week. What struck me the most after I closed the phone (since I mostly read e-books on my phone and laptop) was the author Hu Anyan’s simple and clear way of telling his story through the various positions and work environments he encountered. And in doing so, he depicts everyday life in China in a more clear (to me) manner.

The first observation has to do with the scale described. When he refers to delivery services, it takes time to grasp the size of the city, the size of the building complexes that one has to serve, or the size of the workforce (measured by the thousands). I used Amap, a Chinese rival of Google Maps, to have a rough overview of the city and the neighborhoods described.

One more thing that I keep from the book is the life attitude he holds—an active, realistic one. It seems to me (and I’m aware that I see the world more through this cybernetic lens lately) a more adaptive and resilient way of navigating through the intricacies of life. There are two relevant passages of adaptivity awareness from the author that I like:

“There is a reason that deep-sea fish are blind, and animals in the desert tolerant of thirst—a big part of who I am is determined by my environment and not my nature.” and “But I’m a firm believer in making the most of any situation, and I knew it was my fault for having such high expectations in the first place.”

Both of the preceding points lead to another: the diminishing value of human labor, and thus the dehumanization of work and social interactions. In an era of artificial intelligence and struggling economies, descriptions of how Chinese delivery companies operate appear to reflect our near future. This dystopian present has strict rules and deadlines, trike batteries that must be charged overnight by workers, after-hours company meetings, and reviews from customers who act like kings (“I balked, then instinctively became defensive.” “There should only be one king. I have to serve hundreds of people every day.”) and the compensation that employees should pay in the event of damage or package loss. Furthermore, digital platforms (with different names from Western ones)—e.g., social media, e-commerce, workforce review, and internal HR platforms that send automated care messages following resignation. The different context—Chinese society, different cities, and scale—eliminates noise and emphasizes the point. Employers see a worker’s destiny as nothing more than a function calling—a tool—in an ever-more complex system.

It was a surprise to see the use of pure class arguments like the following (even though it totally makes sense): “This is the lawful right of every worker, not a favor bestowed by capitalists.”

It would be wrong to leave the impression that this is a pessimistic book; at the end, I felt as if I was reading the story of someone my age, with similar music and reading habits, but living in a completely different environment that is becoming somehow similar to ours with each passing day.